Millwork refers to any wood product that is custom milled in a woodworking shop for use in building construction or interior architecture. It typically includes finished wood components that are made to fit specific dimensions or designs, either for functional or decorative purposes.

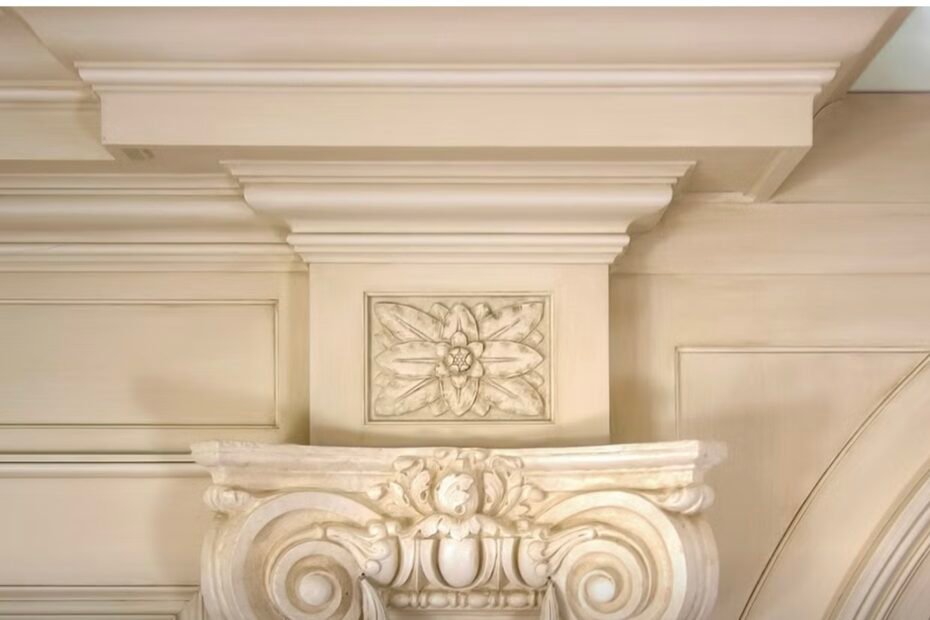

Common examples of millwork include custom doors and window casings, intricately designed staircases and railings, wall paneling, crown moldings, mantels, and trim work. These features do more than add visual appeal—they help define the architectural character of a building while also offering structural support and functional enhancements. Thoughtfully designed millwork brings warmth, craftsmanship, and a sense of permanence to otherwise utilitarian spaces.

The word “millwork” came into use during the Industrial Revolution when powered mills (originally water- or steam-driven) began producing architectural wood components more efficiently and uniformly than hand-crafting alone.

Im going to throw out something controversial here, but you should not use molding designed after 1950.

What!!!

Bear with me, it's not just me saying this and I'll go into the reasons why. Also if you are interested Brent Hull does a great breakdown of this in video format.

Why Are Moldings Designed Pre 1950 Better?

First lets go into the decade preceding 1950's, we have WWII which creates a need in the economy to produce things faster and cheaper than they had been produced.

Production housing is born, or what we call now Trac Home.

Modernism is born: some would say that modernism was a response to the needs of the market as much as it was a move away from the ornamental style of the past.

The driving force of production building is speed and cost and the driving force of modernism is the reduction of ornamentation. Together, both of these trends begin to trickle down into the type of millwork being used and designed.

The advent of things like the clamshell molding used in baseboard was a post 1950 molding introduction.

Architects like Pierre Koenig, Richard Neutra, and John Lautner pushed the modernist aesthetic into the limelight.

There is obviously room to have personal taste when it comes to architecture but there is an interesting phenomenon that has been observed when it comes to modernist architecture. While a building might have had a lot of press and hype at the grand opening. Or the novelty of a bulding like The Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia, in Spain is something to talk about.

What has been observed in cities in the United States, Europe, and around the world is that the historic and classically designed areas of downtown attract the most visitors and consistently draw people to them because they inherently feel more comfortable and personable.

Back to Millwork

The purpose of millwork is the reinforce structural elements and introduce scale and proportion. When we start to look at moulding and millwork from that vantage point, it begins to make more sense why you naturally feel more comfortable in a room that introduces proportion and scale on a human level.

The opposite of this would be the feeling you have when you walk into a very sterile and completely unstyled building, such as a hospital. There is just a different feeling conveyed when proportion is seen and read on a human scale.

What I started to understand when I began studying the molding and profiles used in classical architecture and millwork is that they are used with intention and purpose. While it's tempting to do away with all of the ornamentation, like the modernist and minimalist trends did. We begin to loose something very warm and charming that we get from the classical shapes, we can't get from the unbroken, clean minimal lines of modernism.

Understanding the Ogee Profile

I write briefly about the Ogee profile that is an element that we get from Roman times in my article about how sash windows were produced in the early 1900's.

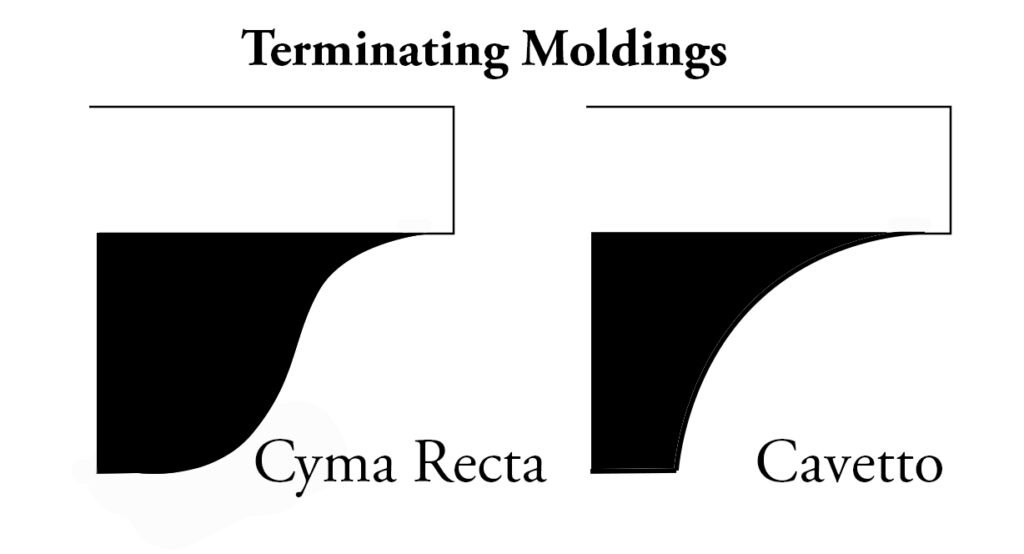

The Ogee profile is categorized 2 ways: Cyma recta and cyma reversa. If you are not familiar with the language of moldings and architecture its easy to be confused as to why you would pick one and not the other. Just like with a language, you can be using the right words but if you use them in the wrong order it won't make any sense.

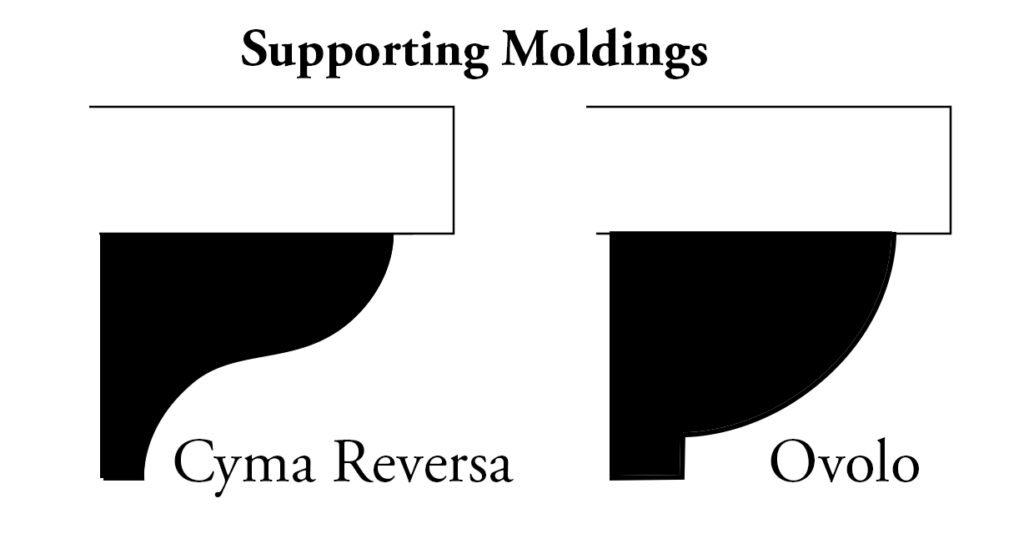

With moldings much of the language is whether they are a terminating molding or a supporting molding.

We can think of the Ogee profile as the combination of two simpler shapes the Ovolo, and the Cavetto.

When there is something big and heavy, you will generally see that the shape of the millwork under it will be an Ovolo shape or in the case of an Ogee it would be the Cyma Reversa, as that profile ends with the Ovolo.

Terminating profiles end with the Caveato, or the Cyma Recta. They can be seen on the tops of wardrobes or in crown molding.

This is just scratching the surface of the topic as the Classical Orders of architecture is a topic much bigger than a single article. You can read about the subject in more detail here,from a company that reproduces traditional molding profiles.

Big Box Stores Mouldings

What separates classically designed Moldings from their modern counterparts?

Before we ask this question, we should also clarify the purpose of moulding. It reinforces structural elements and introduces scale and proportion, but it also creates shadow lines that give depth and contour.

Looking at modern moulding from this perspective, we can begin to analyze why they aren't quite the same as their predecessors.

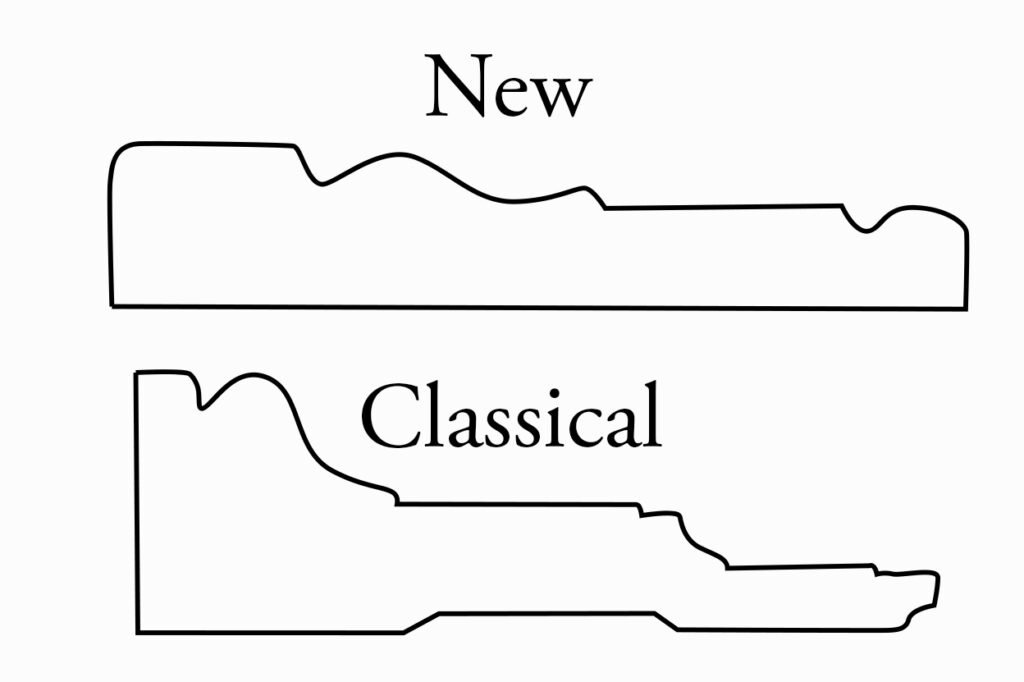

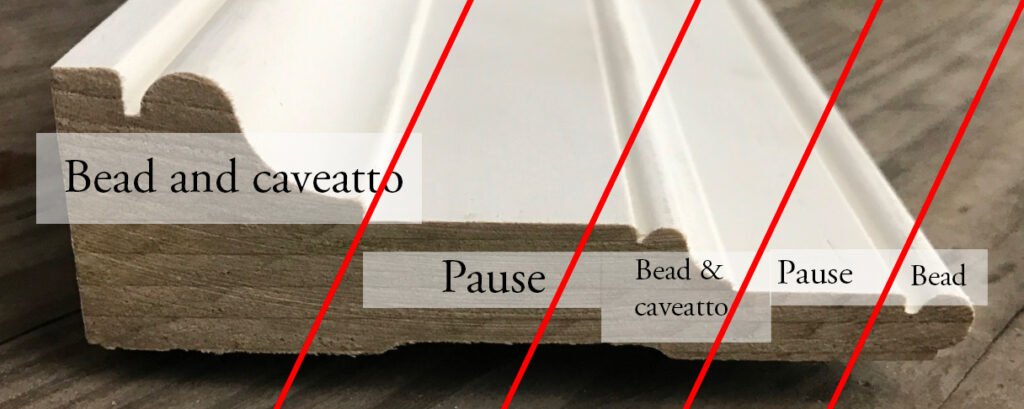

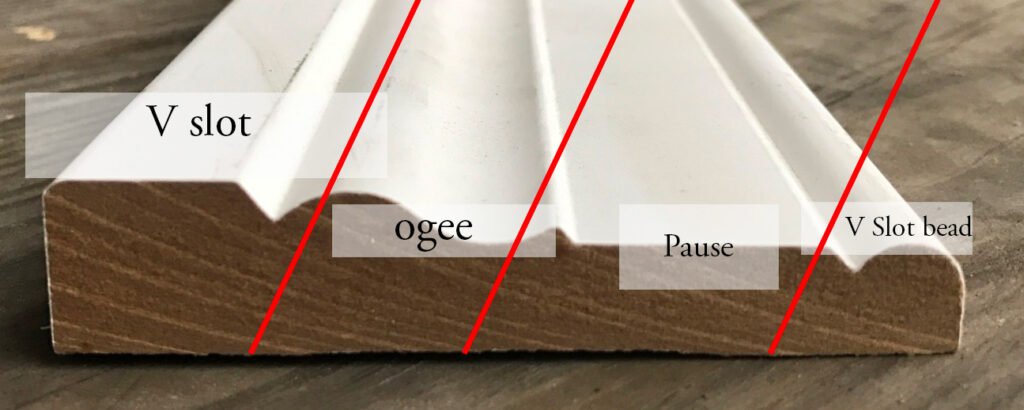

The main difference between the two is the distinction and clarity where one profile ends and creates a stark shadow line.

Also, notice where there are 90º cuts in the classical moulding, they are replaced with a V profile and the overall thickness that a piece of lumber would need to start at to get the classical shape would be almost twice as thick.

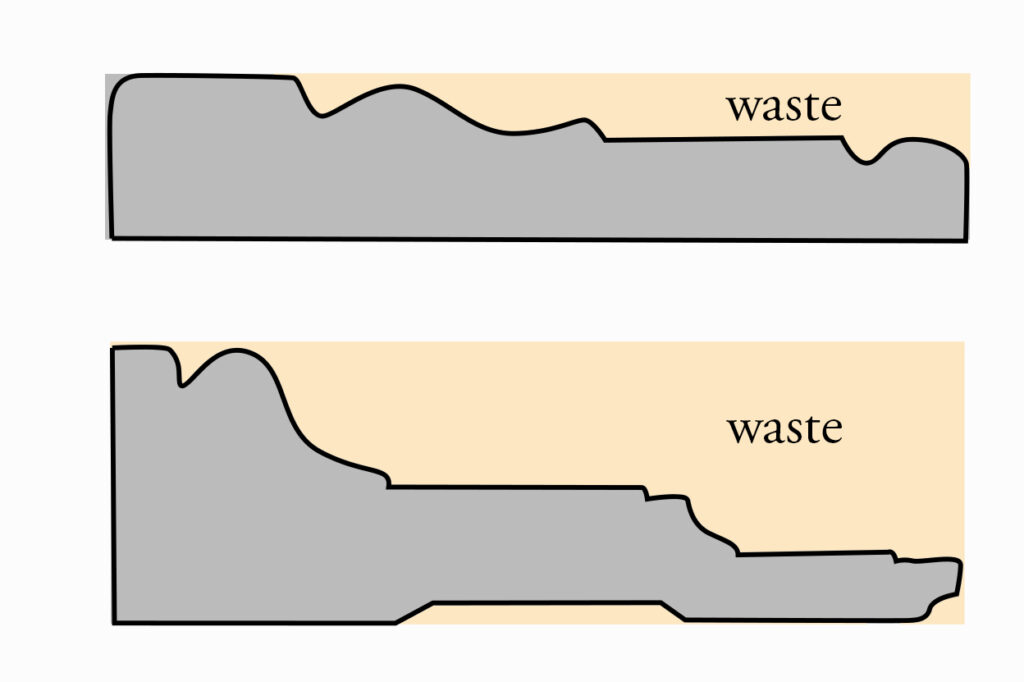

I'm sure this alone had a lot to do with the end product of newly designed mouldings. Let's look at how much waste we would have to mill a classical moulding like this.

There is 50% waste for the classical profile and the stock to start with is almost twice as thick.

You can begin to see how the motivation of speed and cost affects the types of profiles that are mass-produced. It simply is not economical to produce classical mouldings.

Readability Of Mouldings

Another principle that Brent Hull brings up is the readability of mouldings. When we compare the classical profile, there are distinct breaks and pauses. After the cove with a big drop, there is a pause, a flat area, and almost a repeat cove followed by a smaller pause leading into the final bead.

The Classical moulding can almost be seen as fractal, logically mimicking the profile that preceded it, just at a smaller scale.

If we try to read a contemporary moulding this way, it becomes apparent that the fractal rhythmic nature doesn't translate because there is simply not enough contrast between each section. A profile like this, especially from a distance will simply just look like faint shadow lines.

Simply put, mouldings like this tend to be so indistinct they fail to bring in the concept of proportion. I think a big reason people gravitate toward the simple clamshell profile or just completely flat is because they don't understand why you would put moulding in place of another.

Where and When To Use

Obviously another big reason people avoid classical mouldings is that they don't work with the architecture of their home.

Hopefully, after this, you are observing the moulding choices around you and thinking about why certain things look and feel inherently better than others.

Being an active observer will start to give you ideas where certain millwork should be used and why.

It is hard to know when a certain. moulding was designed but it is safe to say that if it's from A Big Orange store, or a Big Blue store, it is a modern redesign. The redesign is there because it costs less to make, it much less milling and stress on the tooling and therefore is going to be marketed to the masses.

If you have a historic home or are working on a historic home its a good idea to look at some other compaies that provide millwork that was based on the designs pre-1950.